Ninth article - Light and Shadow in the Japanese tea ceremony

“Light” and “shadow,” which breathe life into Grand Seiko, are the founding stones of the Japanese sense of aesthetics. Opposite yet reliant on each other to exist, how do Japanese people look upon them, and how have they elevated them to the status of beauty? This column will try to elucidate this sense of aesthetics toward “light” and “shadow,” which have taken root in Japan, through the words of experts in various fields.

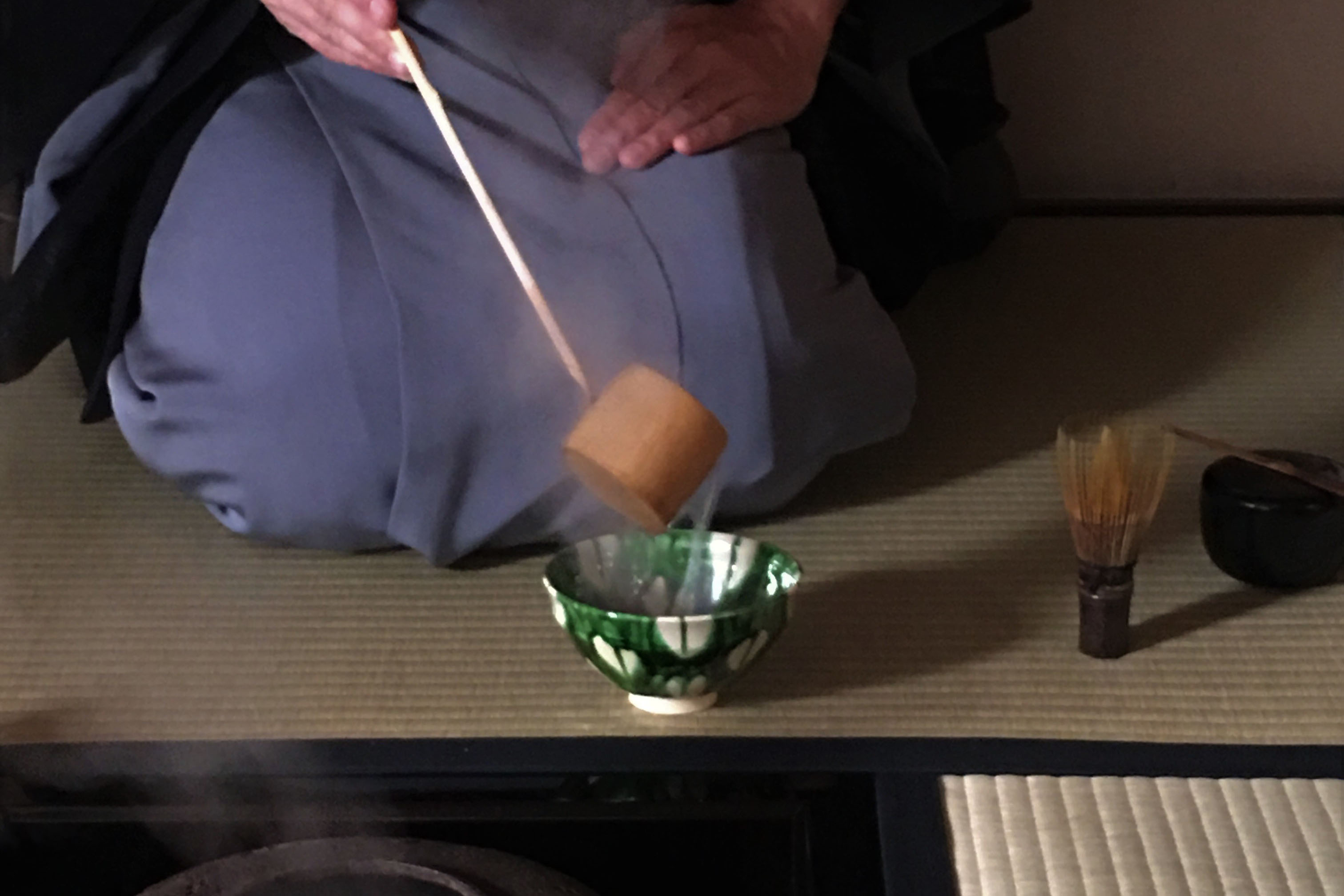

Tea rooms are spaces where you detach your mind and body from the daily hustle and bustle and indulge in an otherworldly experience. In the case of a formal tea ceremony, it starts before noon and takes about four hours to finish. The ceremony involves numerous steps starting with a procedure called sumi-temae, where charcoal is added to the fire to ensure the water is hot, followed by a kaiseki course meal and a bowl of koicha thick tea. Observing each step in hushed silence, the host and guest spend time together in such a small room that their knees almost touch. Four hundred years ago, back when there was no artificial lighting, the only things in the room that hinted at the passage of time were light and shadow. When the tea ceremony started, the sun was high in the sky and sunlight was streaming through the highest point in the center of the window in south-facing tea rooms. However, the sunlight changes height and direction as time passes. Thus, as the evening approaches, you realize that the sunlight is now coming through the bottom of the window from the west side and that its color has become orange. Also, the direction and length of shadows change. Therefore, light and shadow act like a clock in tea ceremonies.

The Japanese tea ceremony in its current form was perfected by Sen Rikyu (1522-1591) in the second half of the 16th century, in the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1603). Rikyu’s teachings are the foundation for the Mushakouji Senke School, of which I am the 15th generation successor. Rikyu brought about a number of revolutionary changes in the Japanese aesthetic sense. In fact, it was he that changed the direction of tea rooms from north to south. Before he did that, it had been the norm to put windows and a small entrance on the north side of the room, which is largely unsusceptible to changes in sunlight. Regardless, Rikyu made tea rooms south-facing. He did not specify the reason for that, but I believe he intended to incorporate the laws of nature, in other words, light and shadow, into tea rooms so that one could sense the flow of time.

National Treasure, Tai-an (Myoki-an temple in Kyoto)

Photo provided by Benrido Co., Ltd.

Furthermore, in the Japanese tea ceremony, light and shadow played a major role in making the tea room become one with people and things and sharpening your focus. You get that sense most strongly when you set foot in Tai-an, the only remaining tea room attributed to Rikyu and a Japanese national treasure, located at Myoki-an temple in Yamazaki, Kyoto. When you place yourself in the cramped two-tatami tea room surrounded by clay walls, it feels more like a cave. Holding in your hand a Raku tea bowl (hand-molded earthenware made by using low-firing temperatures) that looks more like a lump of clay than anything else, made by the first Chojiro (a potter) at the request of Rikyu, the lines between the tea room and utensils, and yourself and other people start to blur. In Rikyu’s time, tea utensils were considered expensive works of art that were worth as much as a castle, and also symbols of power. However, I believe he saw tools just as tools and a tea ceremony as the place where organic entities including humans, flowers, and tea would bestow life upon inorganic objects such as tea utensils. Since the tea room was such a harmoniously unified space overwhelmingly dominated by shadows, a thread of light streaming through the south-facing window was about the only thing that could help you distinguish yourself from others when you calmed your mind and focused. In other words, light and shadow were integral parts of the Japanese tea ceremony.

Similarly, another great example of the light and shadow effect is the “golden tea room” built by Hideyoshi Toyotomi (1537-1598), the feudal lord who completed the unification of Japan, to hold tea ceremonies for the then emperor. A reconstructed version of the tea room was created based on records of that time and is currently exhibited at MOA Museum of Art in Atami. While many people speak of it as if it was just an ostentatious display of wealth by Hideyoshi, it is clear Rikyu had a hand in this and I feel this is very uniquely Japanese. When you are surrounded by that much gold, you feel numb to it. Therefore, the only things you can feel are light and shadow, in the end.

Now that it is placed in a well-lit space, it shines brightly, but the situation must have been completely different 400 years ago when it was in the back of huge wooden structures such as Jurakudai and Osaka Castle. I imagine the golden walls must have shone ever so faintly in those dark spaces as a result of the light from white dust particles that managed to reach them through the south-facing windows. On the other hand, the light from candles placed inside the room must have shone softly like a luminous body. It was more of a minimal and tranquil box than a gorgeous one. Tai-an and the golden tea room might seem like polar opposites to a lot of people today, but I believe they were actually rather similar in that tea was enjoyed in both of them by sensing a ray of light in a sea of shadows.

At the same time, the light and shadow effect also meant giving utensils a special allure that is not possible under monotonous artificial lighting. In other words, the shadows created by the faint light add subtle nuances to the texture of earthenware and lacquerware, and accentuate the uneven surfaces or grain of wood that appear due to exposure to wind and rain. When it comes to the tea room, it might not be an exaggeration to say that light exists so that one can enjoy shadows.

Hatakeyama Memorial Museum of Fine Art

The exhibition room before the museum is closed.

This idea of light and shadow is still alive in the Japanese tea ceremony. You can freely experience that at Hayakeyama Memorial Museum of Fine Art, which is known for its wonderful collection of works of art related to the Japanese tea ceremony, located in Shirokane, Tokyo. It is currently closed due to extensive renovation work, but when I visited, there were big windows in the north and south of the exhibition room, and I was able to see the shadows created by the tea utensils against the background of the natural light softly streaming through the shoji sliding doors. For a fleeting moment, I felt as if I had been transported to a tea room.