Eighth article - Light and Shadow in Edo kiriko glassware

“Light” and “shadow,” which breathe life into Grand Seiko, are the founding stones of the Japanese sense of aesthetics. Opposite yet reliant on each other to exist, how do Japanese people look upon them, and how have they elevated them to the status of beauty? This column will try to elucidate this sense of aesthetics toward “light” and “shadow,” which have taken root in Japan, through the words of experts in various fields.

Edo kiriko refers to a traditional Japanese craft in which geometric patterns are engraved on a glass surface. There are a wide range of Edo kiriko products including sake bottles, sake cups, old-fashioned glasses, bowls, plates, and vases. Many Japanese people may not know this, but Edo kiriko glassware actually has its roots in Europe. Edo kiriko glassware is believed to have originated in Edo (the former name of Tokyo) in 1834, during the late Edo period (1603-1868). At that time, the items were made by hand, but a turning point would come during the Meiji period (1868-1912). A dozen artisans learned glass cutting techniques from a British instructor, and a grinder and a rotating tool for cutting glass surfaces were introduced. At the same time, patterns that had been popular in Britain and Ireland were brought over to Japan. Japanese artisans have gradually added their own touches over the past century while using European glass cutting techniques and patterns as a base. Consequently, Edo kiriko glassware has come to imbue qualities unique to the Japanese aesthetic.

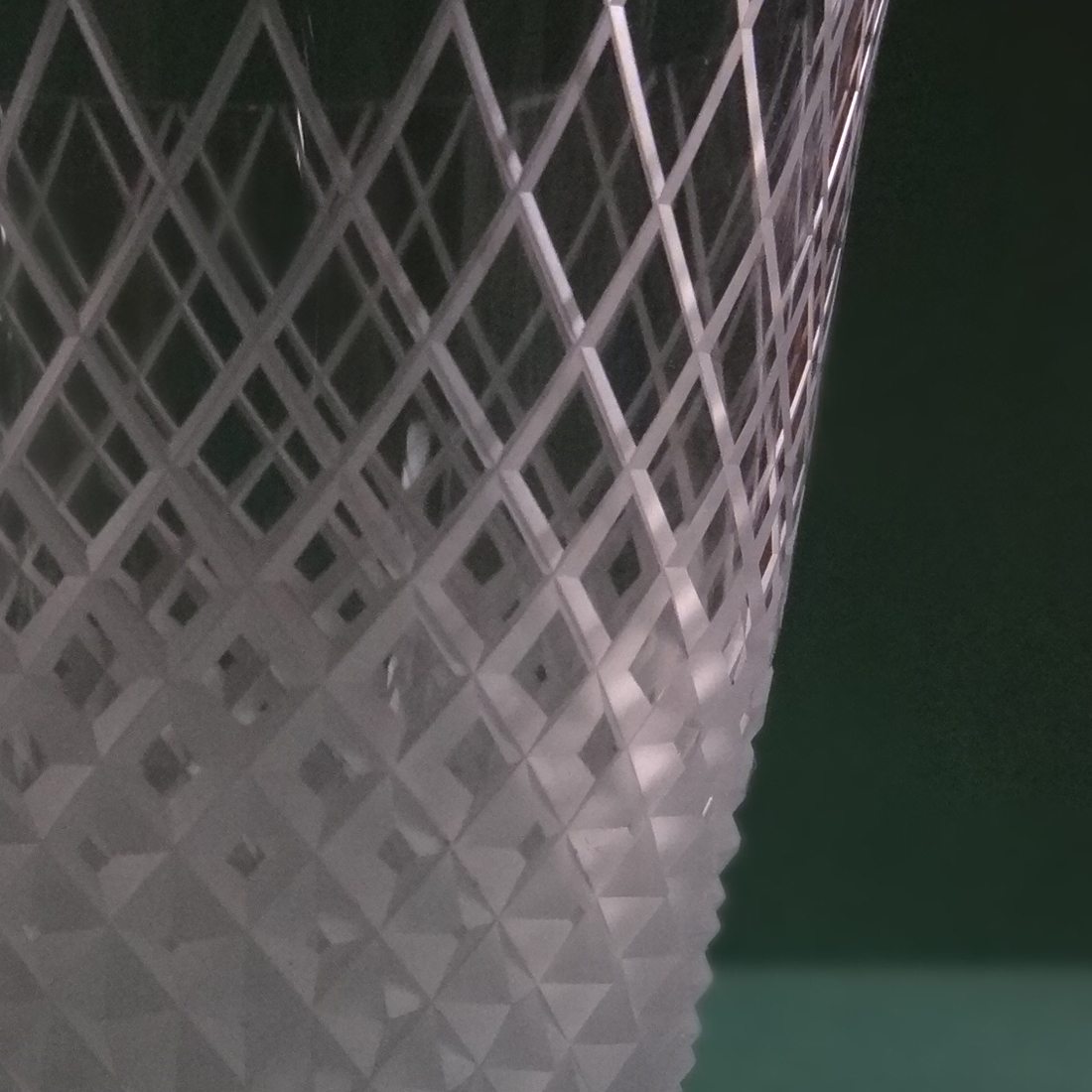

The beauty of Edo kiriko glassware lies in “light.” When glass has a plain surface, light simply passes through it. However, when the surface is cut, light bounces off it, creating a part that falls like a “shadow” next to it. It is because of this that you can see the patterns etched on the surface clearly. The combination of light and shadow varies each time depending on the way the light strikes the surface and the viewing angle. Therefore, the pattern you can see changes as well.

Currently, there are about a dozen representative patterns of Edo kiriko glassware, all of which are geometric ones. Recently, some people have created their own original patterns, but in general Edo kiriko glassware is made by combining traditional patterns. For example, take patterns such as Kiku-tsunagi mon or Kiku-kagome mon. They are very intricate designs, and there is documentary evidence that glasses with complicated patterns like those existed in Europe in the 1850s. However, you would be hard-pressed to find similar ones today. Personally, I believe that is because bold and original cutting patterns or designs that emphasize form are more popular in Europe. In Japan on the other hand, people love products made by highly skilled artisans. I suppose this is why artisans have been able to continue their delicate work and pass their techniques on to their successors for generations. Consequently, those designs are now recognized as Japanese patterns. In Europe, the preference is for rough cut glass, with diffuse reflections from the cut surface shining brilliantly and creating dramatic shadows. With the intricate patterns of Edo kiriko on the other hand, light bounces off the surface more delicately, creating a softer contrast of light and shadow. I feel Japanese taste is reflected in this as well.

This technique is called keshi matting and is used to emphasize the effect of light and shadow. Basically, it is a matte finish like that of frosted glass. It is created by suppressing light reflection and making more shadows instead. When you contrast the opaque matte part with the intricate cutting part where light reflects and shines, it expresses something more Japanese, a wabi-sabi aesthetic sense. A richer expression is achieved by combining a glossy part and a dissimilar matte surface finish.